Lawmakers and omnibus bills: A love-hate relationship

Finally, spring is in the air, heralded by early blooming flowers popping out of the ground to bring relief to winter-weary souls.

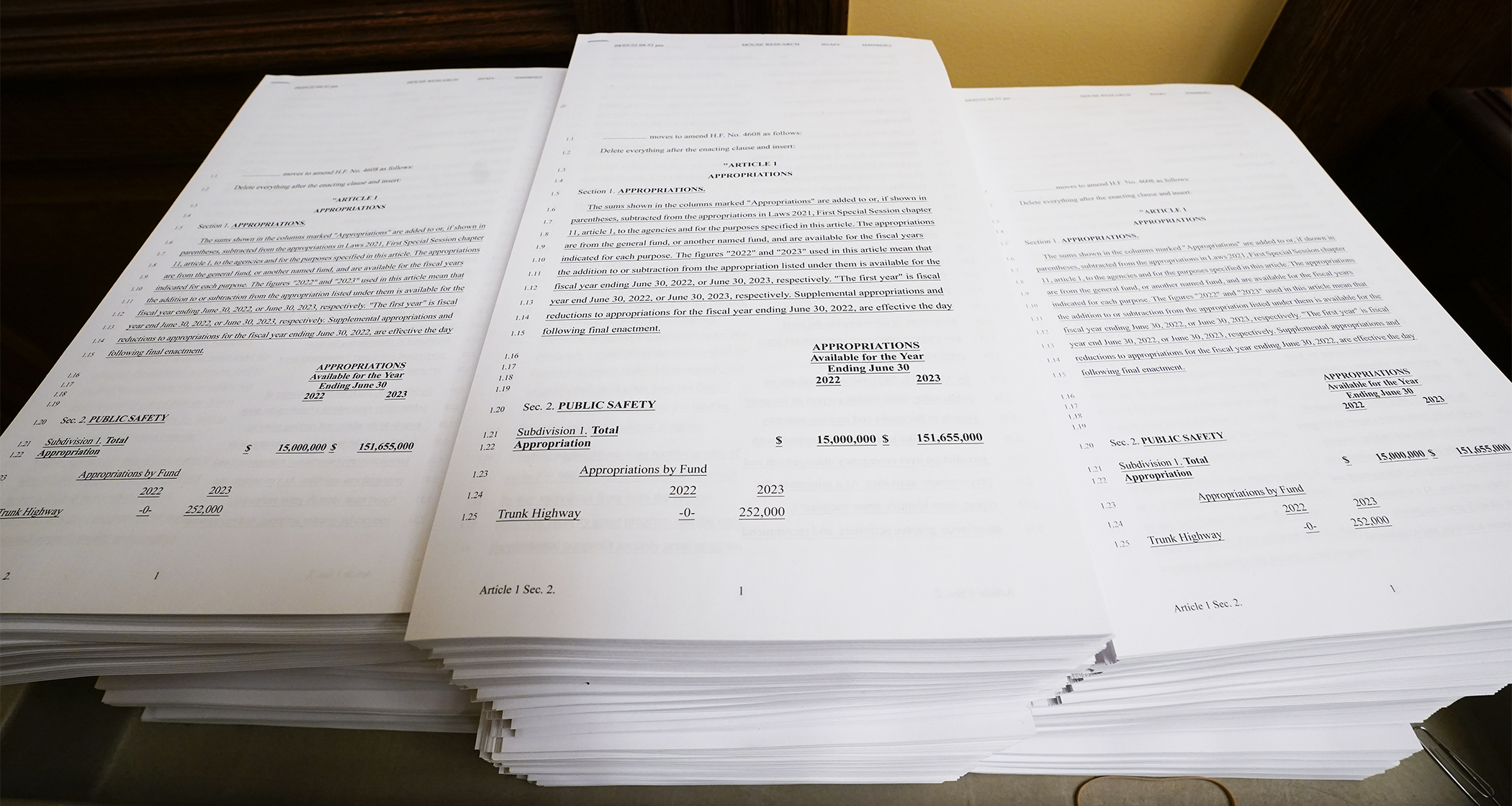

Springtime at the Capitol is also the season of omnibus bills, popping up in conference committees and, hopefully, soon on the House and Senate floors, with a few no doubt headed to the governor’s desk soon.

But also again popping up this year are complaints that — by their very nature — omnibus bills are a terrible way to make new laws.

Omnibus bills are created by lumping together dozens — and sometimes a hundred or more — smaller bills into one large bill.

Sounds efficient and a great help for busy lawmakers with jam-packed schedules, right?

Not necessarily, as for all the efficiencies that come with omnibus bills, they also have several drawbacks — which are frustrating lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.

“Certainly, this is not a DFL nor a Republican problem,” Rep. Pat Garofalo (R-Farmington) said at an April 19 meeting of the House Ways and Means Committee. “This is something that has been going on for multiple years, in fact it’s been going on for multiple decades.”

The problem, Garofalo said, is that the “centralization and consolidation” done to create omnibus bills negates any efficiencies they may have.

“In my opinion, it has reached a tipping point now where we are actually seeing this erode the ability of the legislative branch to function,” he said.

Frustrating, but very efficient

By their very nature, omnibus bills are a very efficient way to move legislation, which results from the ability to take a single vote on many bills in one package rather than individual votes on all the encapsulated bills.

This is no small efficiency. Consider just one of this year’s 11 omnibus bills in the House: the omnibus health and human services supplemental budget bill, and its 870 pages incorporating 89 separate bills.

To process each of those bills individually would require 89 separate yes/no, possibly via roll-call, votes at each committee stop ending with a House Floor roll-call vote for final passage.

Even without considering the additional steps each of these 89 bills must take to reach the governor’s desk, it’s clear that the Legislature would find it very difficult to adopt that process and still finish its business and adjourn on time.

And remember, there are other omnibus bills being considered, which all together encapsulate hundreds of single bills themselves.

Efficient, but very frustrating

For the same reason omnibus bills can speed up the process, they can force lawmakers into taking difficult votes they would rather avoid.

House Speaker Pro Tempore Liz Olson gets help from Legislative Clerk David Surdez with the 1,043-page omnibus health and human services finance bill during the 2019 session. (House Photography file photo)

House Speaker Pro Tempore Liz Olson gets help from Legislative Clerk David Surdez with the 1,043-page omnibus health and human services finance bill during the 2019 session. (House Photography file photo)For every omnibus bill, lawmakers must decide whether there are more items in it they support than they oppose.

But if lawmakers decide to vote “aye” on an omnibus bill because they decide the good in it outweighs the bad, those lawmakers are still on the hook to constituents to explain why they voted for a provision they didn’t really support or even openly campaigned against. Or one that breaks a promise they made to constituents.

Related to this scenario is how Minnesota lawmakers are more and more often tasked with voting on large omnibus bills with scant time to read through them. Sometimes it’s a matter of a few days to go through a conference committee agreement, but sometimes it’s a matter of a few hours. During the frantic moments at the end of a legislative session, it can be mere minutes.

Without enough time to thoroughly understand all of an omnibus bill’s provisions and their ramifications, lawmakers become very nervous about voting for it because of the chance it contains something they really dislike and that could come back to haunt them on the campaign trail.

This frustration is felt more strongly by lawmakers in the minority party because they may not be consulted when the majority party assembles the large omnibus bills. So minority members are more wary of what “gotcha” provisions — also called “poison pills” — might be included by the majority party.

It’s for this reason that astute readers of Session Daily stories will notice that omnibus bills being approved by committees or being passed off the House Floor are almost always advancing along party lines or within a few votes of that.

Efficient and frustrating ... but here to stay?

This isn’t the first time concerns have been raised.

During the 2007 interim and 2008 session, the House Governmental Operations, Reform, Technology and Elections Committee looked at ways to improve the legislative process. ouse House Led by Rep. Gene Pelowski, Jr. (DFL-Winona), the recommendations of a 2008 report include, “The House should discourage omnibus policy bills,” and, “The House should provide more time for members to review omnibus budget bills at each step in the process.”

The chart below shows the first recommendation was not taken to heart. With a few ups and downs, the trend since 2000 is fewer laws being passed each year, in part, because more bills are being clumped into omnibus bills. In 2021 the Legislature passed just 31 bills in the regular session and 14 more in the special session

Without motivation from the top to change the status quo, legislating through omnibus bills will likely remain unless an outside force enters the picture.

That could be the courts, which have occasionally ruled laws unconstitutional because they were enacted through omnibus bills violating the state constitution’s “single subject and title” clause.

Will the third branch flex its muscle?

Forty state constitutions contain a provision requiring a bill to address or contain a single subject, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, and Minnesota is one of them. Article IV, Sec. 17 states: “No law shall embrace more than one subject, which shall be expressed in its title.”

So, why are omnibus bills — which by their very nature often embrace more than one subject — even allowed at all?

Consider, for example, this session’s omnibus agriculture, broadband and housing supplemental finance and policy bill. Could these three topics really be considered one subject?

The answer is yes because legislative leaders say they are. Additionally, an omnibus bill’s title is the broad, “An act relating to state government.”

Written in 2018, Permissibility of Omnibus Bills under the Minnesota Constitution’s Single Subject Clause, Peter Wattson and Ben Stanley of Senate Counsel, Research, and Fiscal Analysis, state, “So long as all of a bill’s provisions have a bona fide connection to a single general subject, they do not violate the single subject requirement. It is only when a challenged provision is actually unrelated to the rest of a bill that the court will strike it down for violating the requirement.”

That happened twice in the aughts, with Minnesota courts ruling in two separate decisions that lawmakers violated the state constitution’s “single subject and title” clause -- and took some laws off the books as a result.

In 2000, the Minnesota Supreme Court ruled a provision in the omnibus tax bill regarding contract labor wages was not sufficiently germane to the title of the bill, which was, “An act relating to the financing and operation of state and local government.”

And in 2005, the Court of Appeals ruled that two articles on firearm provisions in a three-article bill on natural resources were not germane to the bill’s title.

[MORE: Embraced and Expressed: Minnesota’s Single Subject and Title Clause]

But these two cases were the first times courts struck down laws for violating the “single subject and title” clause since 1947, and both cited previous court precedents that a “mere filament” connecting subjects in a bill to its title would satisfy that clause.

Related Articles

Search Session Daily

Advanced Search OptionsPriority Dailies

Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman, husband killed in attack

By HPIS Staff House Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman (DFL-Brooklyn Park) and her husband, Mark, were fatally shot in their home early Saturday morning.

Gov. Tim Walz announced the news dur...

House Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman (DFL-Brooklyn Park) and her husband, Mark, were fatally shot in their home early Saturday morning.

Gov. Tim Walz announced the news dur...

Lawmakers deliver budget bills to governor's desk in one-day special session

By Mike Cook About that talk of needing all 21 hours left in a legislative day to complete a special session?

House members were more than up to the challenge Monday. Beginning at 10 a.m...

About that talk of needing all 21 hours left in a legislative day to complete a special session?

House members were more than up to the challenge Monday. Beginning at 10 a.m...