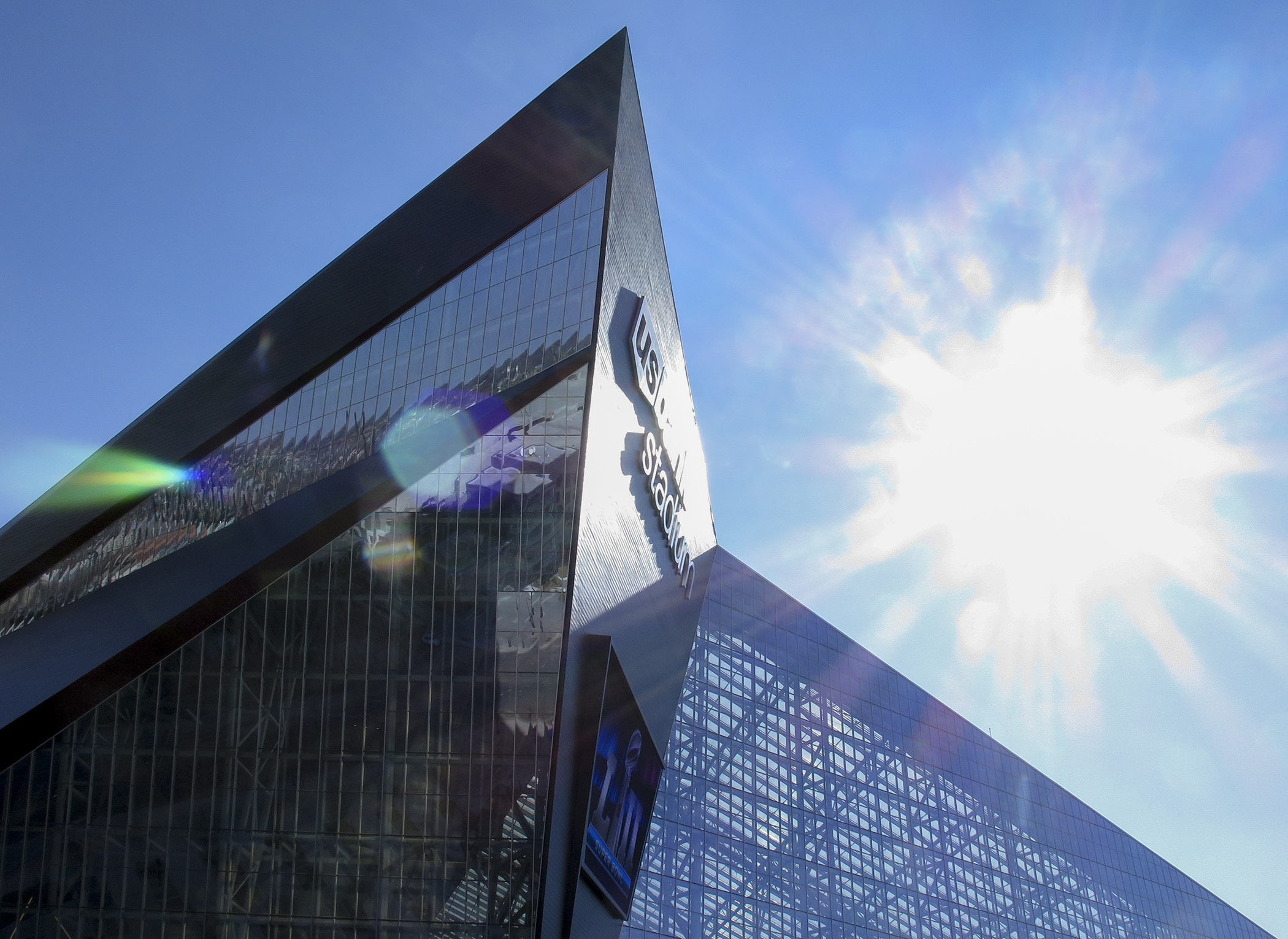

Paying off stadium bonds early could be a touchdown for MN taxpayers, lawmakers say

“Skol” is a celebratory, sometimes deafening, chant 65,000-plus fans do just before each Minnesota Vikings home game.

The funding formula of their playing locale could provide another reason for all Minnesotans to rapidly clap their hands over their head and yell the Norse word for cheers.

Doing the Griddy like all-pro wide receiver Justin Jefferson would be optional.

The stadium reserve fund set up to pay off the bonds to construct U.S. Bank Stadium is almost flush enough with money to pay off stadium debt, said Rep. Michael Nelson (DFL-Brooklyn Park).

“Based on the November [budget] forecast, if we take the money from the stadium reserve, along with $9 million that the governor is proposing from the General Fund, we will be able to pay off the bonds used to finance the stadium 23 years early,” he said. That’s a $226 million savings in aggregate interest costs.

“This is a really good problem to have,” said Rep. Kristin Bahner (DFL-Maple Grove).

By not obliging the governor’s request and waiting until 2024, the state would be charged $30 million in bond interest — a net $21 million penalty for inaction.

[MORE: Stadium financing structure, current bond repayment schedule]

On Thursday, HF288 was laid over by the House State and Local Government Finance and Policy Committee for possible omnibus bill inclusion.

“This bill is also about saving us as legislators from ourselves,” Nelson said. “Too often when legislators see a pot of money growing … we get ideas thinking of all the things we want to spend that money on and not let it be used what it was intended for.”

For example, a 2018 supplemental finance bill proposed using $26 million in excess stadium reserve funds to pay for three veterans’ homes and $4 million to establish a sexual harassment investigations office for state employees. It did not become law.

The 2012 law that led to construction of U.S. Bank Stadium included creation of a reserve account to cover shortfalls or paying down stadium-related debt and expenses.

It was anticipated that much of the state’s up to $348 million investment would come via taxes on charitable gaming, including electronic pull tabs authorized by the law.

While that funding started slowly, it and other sources now bring in significantly more money than is needed to make annual debt service payments on bonds and cover other stadium-related expenses.

If the bonds are paid off, future income from those revenue sources would go to the state’s General Fund.

Not yet in the bill, but something Nelson expressed interest in doing, would be wiping out what Minneapolis still owes for its $150 million toward construction, which minus projected interest now totals about $60 million.

“Simply put, it does not make sense for us to be paying debt on debt that no longer exists,” said Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey, who calls the stadium a statewide asset. When combining outstanding principal plus projected interest, savings to the city would be $12.8 million annually until 2046, money Frey said could be used to help meet other city budgetary needs.

From 2016-2020 the state covered the city’s share of its expected contribution, which, per the law, first went to paying off construction bonds for the Minneapolis Convention Center. “Last year, they started paying that [state] money back,” Nelson said.

“There are ongoing conversations to be had,” said Rep. Ginny Klevorn (DFL-Plymouth). She is the committee chair.

Nelson emphasized the bill would have no benefit to the Vikings, other than the law requires U.S. Bank Stadium be operated in a “first-class manner.”

A capital improvement fund would remain to keep the facility up to date, unlike what happened with the Metrodome.

“I don’t want to see us building another stadium in my lifetime,” said Nelson, a retired carpenter. “And I hope to live a long time. Well, at least another 30 years.”

Related Articles

Search Session Daily

Advanced Search OptionsPriority Dailies

Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman, husband killed in attack

By HPIS Staff House Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman (DFL-Brooklyn Park) and her husband, Mark, were fatally shot in their home early Saturday morning.

Gov. Tim Walz announced the news dur...

House Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman (DFL-Brooklyn Park) and her husband, Mark, were fatally shot in their home early Saturday morning.

Gov. Tim Walz announced the news dur...

Lawmakers deliver budget bills to governor's desk in one-day special session

By Mike Cook About that talk of needing all 21 hours left in a legislative day to complete a special session?

House members were more than up to the challenge Monday. Beginning at 10 a.m...

About that talk of needing all 21 hours left in a legislative day to complete a special session?

House members were more than up to the challenge Monday. Beginning at 10 a.m...