'Hello, I'm your representative. Is this your abandoned property?'

Rep. Joe Atkins (DFL-Inver Grove Heights) wants House members to receive the names of people and businesses in their districts who have unclaimed property sitting in state coffers and warehouses.

The Commerce Department estimates the agency is holding about 3.4 million pieces of abandoned property belonging to 3.7 million owners. Indeed, nearly one in six House members would find their own names on these lists, the department’s online database shows.

Some abandoned property may not amount to much, but $100 or more is waiting in the state’s unclaimed property fund for one in every 20 Minnesotans.

That rate is twice as high among House members, where at least 15 — more than one in 10 — has unclaimed properties worth more than $100. Three representatives, all from Minneapolis, account for 20 of the listed 44 properties of any value belonging to 21 members.

By statute, banks, insurance firms and other companies turn over property to the state after they have tried and failed to find the rightful owners. The property is mostly in the form of money or insurance dividends and the like, but it also can include physical objects such as items from abandoned safety deposit boxes.

Atkins’ bill, HF1693, aims to amp up efforts to return $650 million worth of abandoned property in state accounts and storage spaces. He is one of a handful of DFLers with legislation included in HF843, the omnibus job growth and energy affordability bill that passed the House April 22.

Not Rockfordesque

Atkins credits a quote by Rep. Greg Davids (R-Preston) in a 2013 Politics in Minnesota Capitol Report news article (“The numbers on unclaimed property should be going down, not up”) with inspiring his quest to improve the state’s record on returning unclaimed property.

Why require lists for legislators? “It worked for me,” Atkins said in an interview — acknowledging that not all members would follow through with contacting constituents on their list.

Atkins’ constituents are $306,229 richer (as of April 20) from an outreach experiment he conducted this session. He speculated a spike in claims to the state this spring are in part due to his efforts. The big fish so far is a couple with $142,000 coming from an annuity. The company had been trying to get the money to them for 13 years — but at a street address that was one digit off.

The Atkins method (“nothing fancy — it wasn’t the Rockford Files”) was to spend 10 minutes a day for three weeks tracking down the 2,009 people and businesses in District 52B that the Commerce Department told him had $3.9 million in abandoned property.

His tools: Google, WhitePages.com, U.S. mail, telephone, email and Facebook. Atkins, who isn’t on Twitter and says he’s no social-media whiz, nonetheless waged a successful online outreach campaign.

Since the start of session, Atkins’ 10 posts about local unclaimed property on his Facebook page have attracted 234 likes, 91 shares and 78 comments — an “avalanche” of interest, Atkins said. Among the comments:

- “I'm waiting for a $9,000 life insurance policy my parents had that we didn't know about ... Thanks!”

- “I have under $100 from an old serving job from college. Bet it's my last paycheck at $5.15/hr, after taxes I bet it's $15!”

- “I found significant amounts for a niece, three nephews, a cousin, a son, and a granddaughter ... all in a matter of minutes.”

- “I had 300 dollars sitting in an account from when I was a child.”

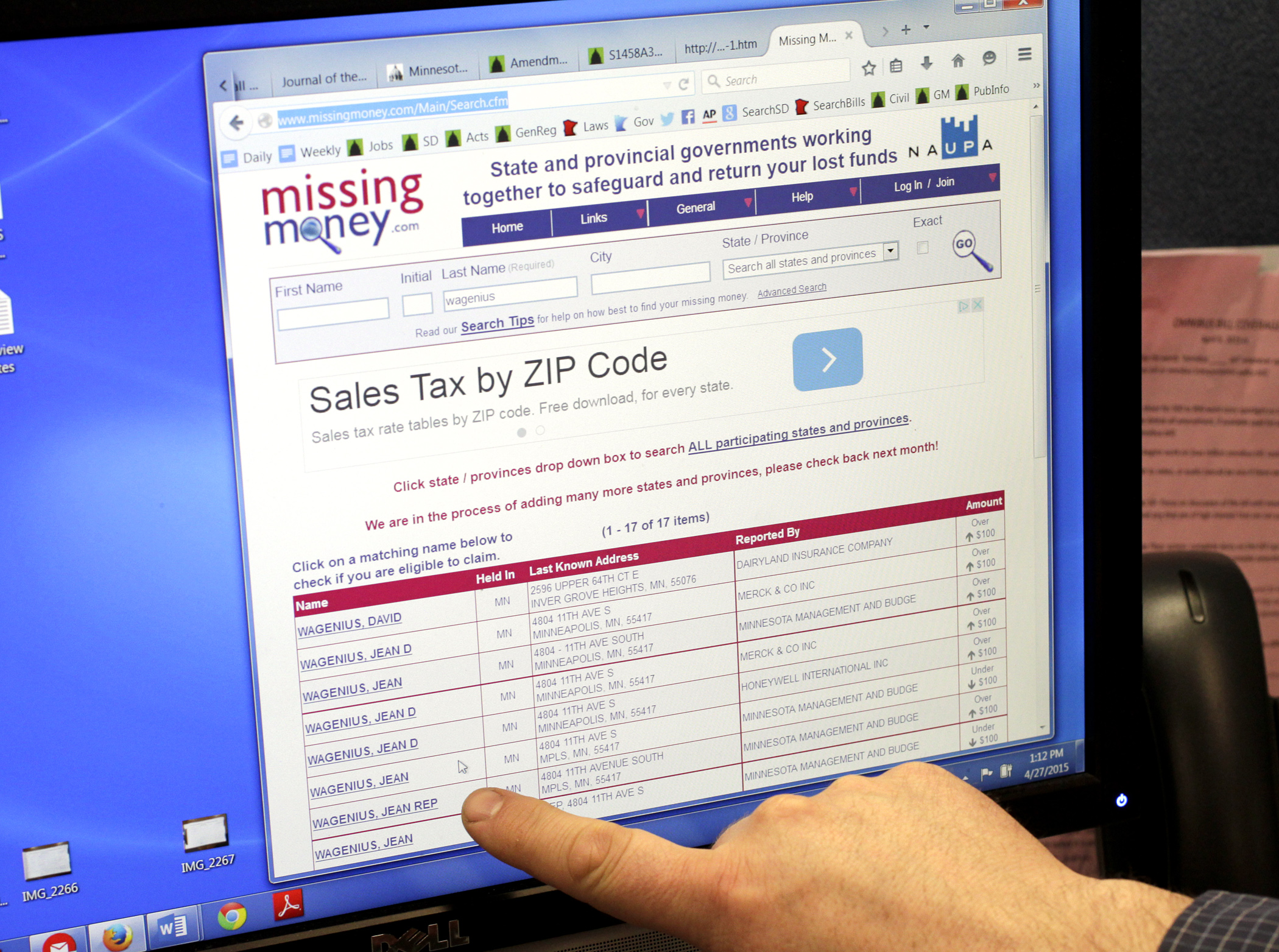

MissingMoney.com

Several constituents wondered about the website Atkins’ posts directed them to: MissingMoney.com. “I know the website has a cheesy name, but it really is the official unclaimed property site used by 26 states,” Atkins told followers on Facebook.

The Commerce Department began using MissingMoney.com in 2003, a move away from newspaper ads codified two years later when the Legislature repealed a statutory requirement for public notice in print media. In 2012, the department began processing some claims electronically via the MissingMoney.com site, with further streamlining in 2014-15 that included rewriting claims forms to make them easier to understand.

The department’s tally of processed claims this fiscal year: 16,409. “They have stepped up their efforts,” Atkins told the House Commerce and Regulatory Reform Committee March 18.

What the bills say

The Commerce Department backs Atkins’ original language in HF1693, the agency said in a statement, and “is committed to working with all parties on the language currently in HF843 to ensure that our shared goal of returning unclaimed property to Minnesotans is met.”

The omnibus job growth and energy affordability bill drops a mandate that the department hire two full-time equivalent staff positions dedicated to reuniting property with its rightful owners. Instead, the omnibus bill would require the Commerce Department to contract with a vendor. The state (not the property owner) would pay the vendor as much as 7 percent of the value of any returned abandoned property, up to $500,000.

Besides the vendor contract and annual lists for legislators, the legislation would require the department to:

- post a list of owners of unclaimed property on the department’s website, in alphabetical order and by county, updated at least three times a year;

- publish a list of people and businesses owning unclaimed property valued at $500 or more in newspapers serving every Minnesota county, and on those newspapers’ websites;

- spread the word by other means and media, including broadcast media, the Internet, and social media; and

- report annually to the Legislature how the department is using its budget for public notices (at least 15 percent of the unclaimed property division’s allocation).

Related Articles

Search Session Daily

Advanced Search OptionsPriority Dailies

Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman, husband killed in attack

By HPIS Staff House Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman (DFL-Brooklyn Park) and her husband, Mark, were fatally shot in their home early Saturday morning.

Gov. Tim Walz announced the news dur...

House Speaker Emerita Melissa Hortman (DFL-Brooklyn Park) and her husband, Mark, were fatally shot in their home early Saturday morning.

Gov. Tim Walz announced the news dur...

Lawmakers deliver budget bills to governor's desk in one-day special session

By Mike Cook About that talk of needing all 21 hours left in a legislative day to complete a special session?

House members were more than up to the challenge Monday. Beginning at 10 a.m...

About that talk of needing all 21 hours left in a legislative day to complete a special session?

House members were more than up to the challenge Monday. Beginning at 10 a.m...