Executive Summary

This publication describes the state tax treatment of Social Security income, shows the income levels at which

taxpayers are subject to taxes on Social Security benefits, and provides a survey of the tax treatment of Social Security in other states.

It also provides some brief historical context on the federal exclusion and state subtraction.

Most Minnesota residents receiving Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance

(OASDI) Social Security benefits do not pay state income taxes on their benefits.

House Research modeling for tax year 2025 implies that:

- Of the estimated total benefits paid to Minnesota residents, approximately 20 percent will be subject to tax.

- Approximately 29 percent of resident returns with Social Security benefits will pay tax on that income.

- After accounting for residents who do not file state tax returns, about 21 percent of Minnesota households receiving Social Security benefits pay tax on their benefits.

Last Updated: January 2025

Exemption from Minnesota Income Tax

Part or all of a taxpayer’s Social Security benefits are exempt from Minnesota’s income tax

Federal law exempts from taxation 15 percent to 100 percent of each taxpayer’s Title II Social Security benefits,

also known as Old-age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance (OASDI) benefits.

Minnesota’s income tax incorporates the federal exemption and provides an income-tested state subtraction that exempts from state tax part or all of

the taxpayer’s benefits that are subject to federal tax. For tax year 2025, the subtraction begins to phase out at $108,320 of adjusted gross income

(AGI) for married joint returns and $84,490 of AGI for single and head of household returns. These thresholds increase each year based on inflation.

The table below shows the structure of the phaseout.

Table 1: Minnesota’s tax treatment of Social Security benefits, tax year 2025

| |

Married taxpayers filing joint returns |

Single or head of household taxpayers |

Married taxpayers filing separate returns |

| Social Security fully tax exempt |

$108,320 or less |

$84,490 or less |

$54,160 or less |

| Some federally taxable benefits subject to state tax |

$108,321 to $144,320 |

$84,491 to $120,490 |

$54,161 to $72,160 |

| All federally taxable benefits subject to state tax |

$144,321 or greater |

$120,491 or greater |

$72,161 or greater |

For most filers, a taxpayer’s subtraction is reduced by 10 percent for each $4,000 of AGI (or fraction of $4,000) above the phaseout. For example,

a married taxpayer with $115,000 of AGI would receive a subtraction for 80 percent of the taxpayer’s federally taxable Social Security benefits

because the taxpayer’s AGI is two increments (or partial increments) of $4,000 above $108,320.

Measuring the extent of the remaining tax on Social Security income

The extent to which Social Security benefits are subject to Minnesota income tax depends on the measure used. There are at least three ways to

measure the extent of Social Security taxation in the state:

- The percentage of tax returns with Social Security benefits that paid at least some tax on thei benefits

- The percentage of resident beneficiaries that paid at least some tax on their benefits

- The percentage of resident Social Security benefits that are subject to tax in Minnesota

Returns and Beneficiaries Paying Minnesota Tax on Social Security Benefits

Among taxpayers filing returns, House Research modeling estimates1 that about 181,800 resident returns will pay at least some Minnesota

tax on their Social Security benefits in tax year 2025. That represents about 29.3 percent of all resident returns expected to be filed in

Minnesota with Social Security benefits.

However, research by the Social Security Trustees suggests that just over half of Social Security recipients pay federal income tax on their

Social Security benefits, and only about 72 percent of beneficiary families file income tax returns.2 If the federal estimate of 72 percent of

beneficiaries’ families filing returns is correct, that would imply that 863,100 total families will receive Social Security benefits in 2025,3

and about 21.1 percent of Minnesota families with a Social Security beneficiary will pay state income tax on that income.

Table 2: Minnesota resident returns, returns with Social Security benefits, returns that paid state income tax, and total beneficiaries, estimates for tax year 20254

| Estimated total resident returns |

Estimated resident returns filed with Social Security income |

Estimated total households that include a beneficiary5 |

Resident returns expected to pay state tax on Social Security income |

| 2,771,500 |

621,500 |

863,100 |

183,400 |

Based on the data in the table above, the estimated share of returns paying any Minnesota income taxes on Social Security benefits is:

- 6.6 percent of all Minnesota resident returns;

- 21.1 percent of the estimated total Minnesota households receiving Social Security benefits; and

- 29.3 percent of Minnesota resident tax returns with Social Security income.

Social Security Benefits Subject to Minnesota Income Tax

The most recent year for which a sample of state income tax records is available is tax year 2022. That year precedes the significant expansion

of the state Social Security subtraction that was enacted in the 2023 omnibus tax bill, which was effective for tax year 2023. As a result,

the data in this report is modeled data for tax year 2025 rather than data reported on returns, as was presented in a previous version of

this publication.

House Research modeling for tax year 2025 estimates that about 621,500 resident returns will report about $20.6 billion in Social Security benefits.

Of that amount, about 55.1 percent will be taxable under federal law, and 24.0 percent will be taxable in Minnesota. However, this likely overstates

the total share of benefits subject to tax, because some taxpayers with Social Security income do not have an income tax filing requirement. In the

most recent year for which data is available (tax year 2022), about 81.4 percent of Social Security income was reported on resident returns.6 If a

similar ratio continues in 2025, a total of $25.3 billion in benefits will be paid to Minnesota residents, which would imply that approximately 19.5

percent of Social Security benefits in Minnesota will be subject to tax in 2025.

The lowest-income taxpayers pay very little tax on their Social Security benefits, due largely to the federal exclusion. About 99 percent of the

Social Security benefits subject to Minnesota income tax are earned by taxpayers with at least $75,000 of federal adjusted gross income (FAGI), and

about 87.5 percent is from taxpayers with at least $125,000 of FAGI.

Table 3: Social Security benefits taxable federally and in Minnesota,

Minnesota residents filing returns only, estimated amounts for tax year 2025

| Federal Adjusted Gross Income |

Social Security benefits (millions $) |

Federally taxable benefits (millions $) |

Benefits taxable in Minnesota (millions $) |

% of benefits taxable federally |

% of benefits taxable, Minnesota |

Share of total taxable benefits |

| Less than $25,000 |

$4,326 |

$154 |

$0 |

3.6% |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| $25,000 to $50,000 |

2,989 |

919 |

0 |

30.7 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

| $50,000 to $75,000 |

2,886 |

1,725 |

2 |

59.8 |

0.1 |

0 |

| $75,000 to $100,000 |

2,734 |

2,114 |

113 |

77.3 |

4.1 |

2.3 |

| $100,000 to $125,000 |

2,201 |

1,828 |

503 |

83.0 |

22.9 |

10.2 |

| $125,000 to $150,000 |

1,798 |

1,527 |

1,248 |

84.9 |

69.4 |

25.3 |

| $150,000 and greater |

3,620 |

3,071 |

3,071 |

84.8 |

84.8 |

62.2 |

| Total |

$20,555 |

$11,339 |

$4,936 |

55.2% |

24.0% |

100.0% |

| Tax Year 2025 Estimates using the House Income Tax Simulation

model, version 7.5. Compiled by House Research. |

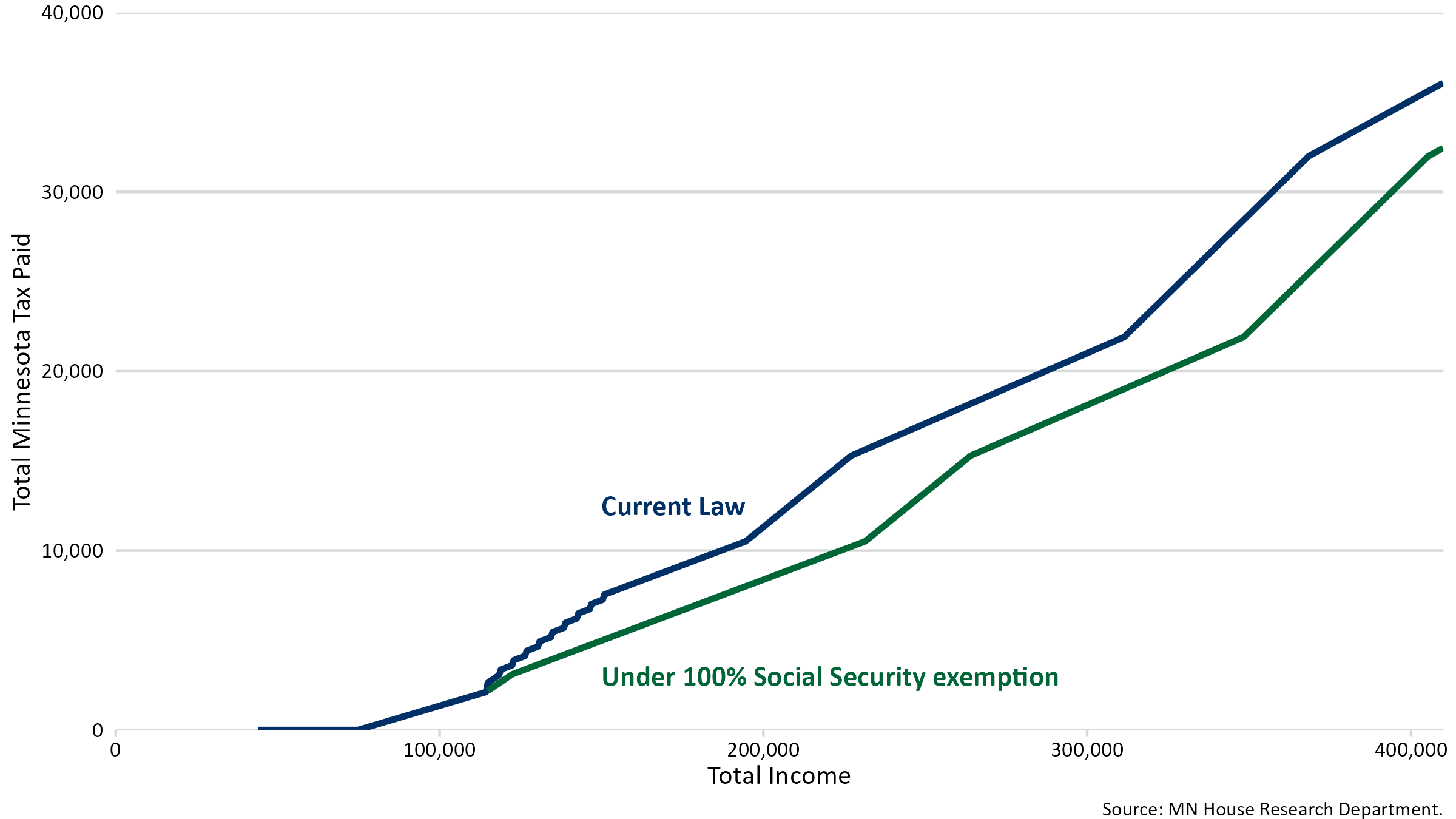

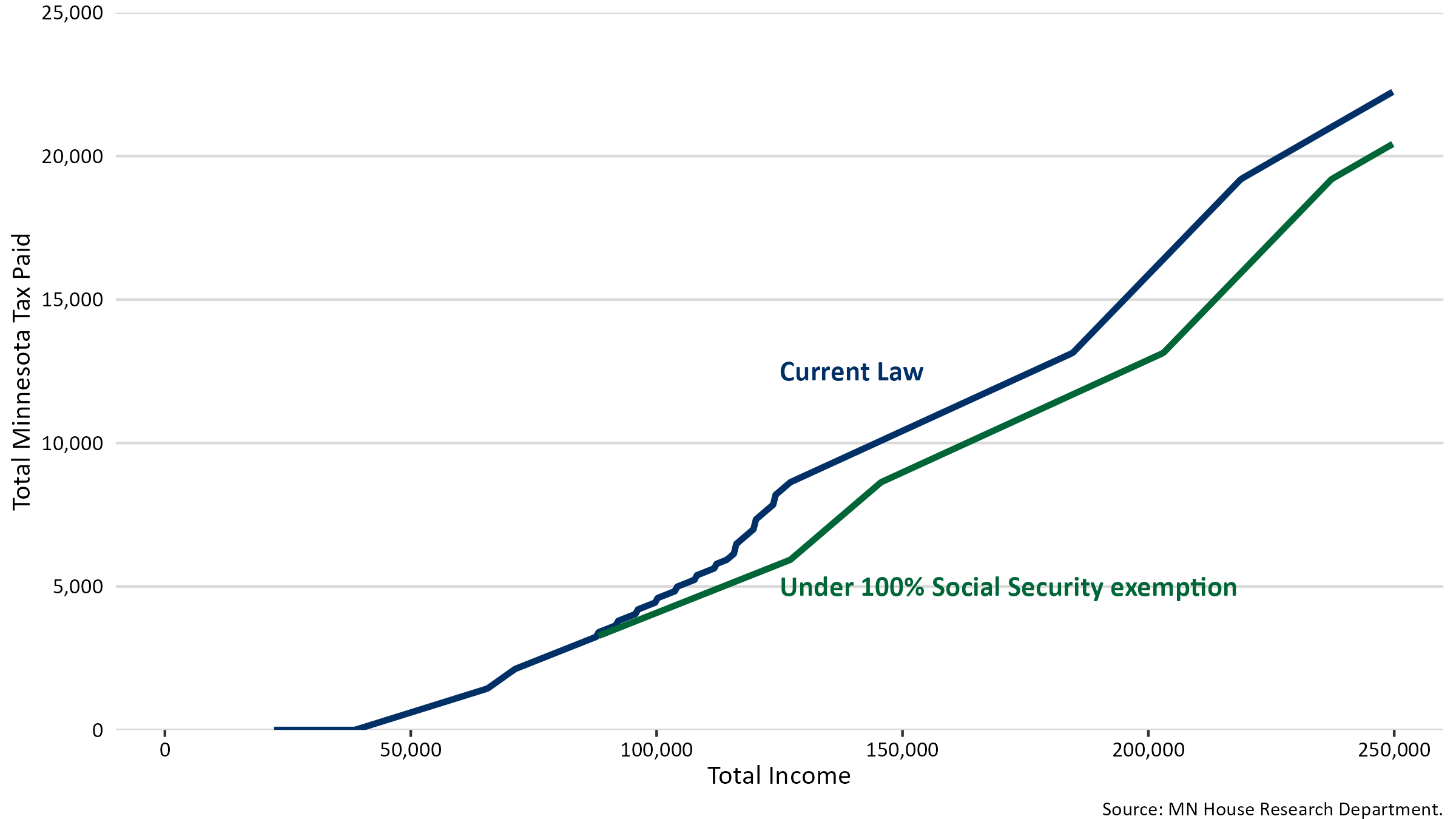

Figures 1 and 2 below show the amount of tax paid on Social Security benefits as taxpayer income increases. Both figures assume a

“typical” Social Security benefit amount for Minnesota. Figure 1 describes the situation for married taxpayers filing joint returns,

and figure 2 describes the situation for single taxpayers.

Figure 1 shows the amount of tax paid for a married joint taxpayer with $43,400 of Social Security benefits. This number is a rounded estimate of

twice the average annual benefit paid to Minnesota residents in 2023, which is the most recent year for which data was available.7 The graph relies

on certain assumptions about the taxpayer’s situation, including that the taxpayers both took the senior standard deduction (for a total standard deduction

of $33,000 for two senior taxpayers filing a joint return) and had no other above-the-line deductions or state subtractions.

The blue line in figure 1 shows tax under current state policy for tax year 2025, and the green line shows the tax under a full exemption for

Social Security income. As the graph shows, a taxpayer with an average Social Security benefit does not pay any state income tax until they

have total income ($43,400 in Social Security plus other income) of $74,900. This is because of the combination of the state standard deduction and the

federal exclusion for Social Security income, which starts at 100 percent of benefits and scales down to 15 percent of benefits as income increases.

The green line in the graph below shows the amount of tax that would be paid if 100 percent of Social Security benefits were excluded from income tax

under state law—for the above-described taxpayers, that policy begins to reduce tax once total income reaches $114,900. The zig-zagged section of the blue

line reflects the state phaseout of the Social Security subtraction under current law. The differing slopes of the two lines reflect the changes in marginal tax rates.

Figure 1: State income tax, married taxpayers with average Social Security benefits

Current law vs. 100% Social Security subtraction, tax year 2025

For a taxpayer with $43,400 of Social Security benefits, the largest possible tax benefit from a 100 percent Social Security subtraction

(represented by the gap between the blue and green lines) is $3,633 (85 percent of $43,400, multiplied by the top marginal rate of 9.85 percent).

Figure 2 shows the amount of tax paid for a single taxpayer with $21,700 of Social Security benefits, as was described above; this number

is a rounded estimate of the average annual benefit paid to Minnesota residents.8 The graph similarly relies on certain assumptions about the

taxpayer’s situation, including that the taxpayer took the senior standard deduction ($16,950 for senior taxpayers filing as single) and had

no other above-the-line deductions or state subtractions.

The blue line in figure 2 shows tax under current state policy for tax year 2025, and the green line shows the tax under a full

exemption for Social Security income. As the graph shows, a single taxpayer with an average Social Security benefit does not pay any state

income tax until they have total income ($21,700 in Social Security plus other income) of $38,700. Again, this is because of the combination of

the state standard deduction and the federal exclusion for Social Security income. For single taxpayers with $21,700 of Social Security benefits,

that policy begins to reduce tax once total income reaches $88,200.

Figure 2: State income tax, single taxpayers with average Social Security benefits

Current law vs. 100% Social Security subtraction, tax year 2025

For a taxpayer with $21,700 of Social Security benefits, the largest possible tax benefit from a 100 percent Social Security subtraction (represented by the gap between the blue and green lines) is

$1,817 (85 percent of $21,700, multiplied by the top marginal rate of 9.85 percent).

The Reason for Taxing Social Security Benefits

Social Security benefits are partially taxed at the federal level, and the federal tax treatment flows through to Minnesota’s income tax. Minnesota’s income tax uses federal adjusted gross income (FAGI)

as the starting point for its state tax calculations. For taxpayers whose benefits are taxable federally, FAGI includes the taxable portion of their benefits, meaning Social Security is included in

the income definition that is the starting point for Minnesota’s income tax.

State and federal policymakers chose to tax Social Security benefits because they are income, and policymakers decided to tax them like other sources of income. One value that

policymakers consider in tax policy is horizontal equity—the idea that taxpayers with the same incomes should pay the same amount of tax, regardless of the source of the income.

These horizontal equity concerns were part of Congress’s rationale for subjecting benefits to tax in 1983. The Congressional Research Service (CRS) quotes the House Ways and Means

Committee as arguing in 1983 that “social security benefits are in the nature of benefits received under other retirement systems, which are subject to taxation to the extent they

exceed a worker’s after-tax contributions.”9

CRS also raises a second reason that benefits are taxed—to raise revenue. The Social Security Amendments of 1983 devoted the revenue raised by taxing Social Security to improving the

Social Security program’s solvency, and some states conformed to the federal treatment as a way to raise revenue.

Double Taxation of Benefits; Comparison with Other Forms of Retirement Savings

The tax treatment of private pension income and retirement savings accounts is designed to avoid double taxation. Retirement income is typically taxed either when the income is saved/contributed, or at the time the income is received, but not both. For example, traditional individual retirement accounts (IRAs) provide contributions are made pretax and retirement distributions are taxable, while contributions to Roth accounts are taxed in the year made and qualifying distributions are not taxed. Traditional defined benefit pensions are taxable but retirees are allowed to recover a portion of their after-tax contributions tax free, each year under actuarial estimates of the amount contributed.

Congress designed the federal tax treatment of Social Security benefits to mimic the treatment of defined benefit pensions—in other words, Congress intended for benefits to be taxed only to the extent that they exceed a percentage of benefits received, determined actuarially to allow recovery of employee taxes/contributions on average. Because the wages that pay Social Security taxes (FICA taxes) are subject to income tax, they are analogous to post-tax employee contributions to a defined benefit pension plan.

In 1993, when the maximum share of Social Security benefits subject to taxation was increased to 85 percent, the Social Security Actuary estimated that the average ratio of employee payroll tax contributions to benefits received was about 4 percent to 5 percent for current beneficiaries. For workers entering the workforce in 1993, the Actuary estimated that the ratio was about 7 percent. The group with the highest estimated ratio of taxes paid to benefits received—single, highly paid males—was about 15 percent. The federal exclusion for Social Security benefits was consequently set at 15 percent to ensure that the taxpayers with the highest ratio of taxes paid to benefits received were not subject to double taxation.10 The Social Security Actuary has not published updated estimates of the ratio of taxes paid to benefits received, so it is unclear if taxpayers with a high ratio of taxes paid to benefits received are currently subject to a small amount of double taxation.

Minnesota's "alternative subtraction"

Current Minnesota law allows taxpayers to use an “alternative subtraction” based on the way that the state’s Social Security subtraction was calculated prior to tax year 2023.

House Research modeling implies that by tax year 2025, this “hold harmless” provision will not benefit any Minnesota taxpayers, because the alternative subtraction parameters are not

indexed for inflation. As a result, after two years of growth in the main Social Security subtraction income thresholds, this provision is no longer beneficial to any taxpayers.

The Federal Social Security Exclusion

The starting point for calculating Minnesota’s income tax is Federal Adjusted Gross Income (FAGI), which is a federally defined measure of income minus certain exclusions (also known as "above-the-line" deductions). Any income that is not included in FAGI is not subject to Minnesota’s income tax.

Federal law allows taxpayers to exclude a portion of their Social Security benefits when calculating FAGI, and this exclusion consequently flows through to Minnesota’s income tax. The formula used to calculate the exclusion is complicated; the amount of a taxpayer’s exclusion depends on the taxpayer’s provisional income (provisional income is discussed in detail below). Social Security benefits included in FAGI are subject to federal tax in the same manner as ordinary income (e.g., wage, salary, and interest income).

The federal Social Security exclusion has three tiers. Depending on the taxpayer’s provisional income, the federal exclusion is either 100 percent, 50 percent, or 15 percent of benefits. The table below shows the income ranges for the different tiers.

Table 4: Federal Social Security exclusion tiers

| Married Couple’s Provisional Income |

Single Filer’s Provisional Income |

Exclusion Percentage |

| $32,000 or less |

$25,000 or less |

100% |

| Tier 1: $32,000 to $44,000 |

Tier 1: $25,000 to $34,000 |

50% |

| Tier 2: $44,000 or greater |

Tier 2: $34,000 or greater |

15% |

Taxpayers with provisional income below the first tier threshold are allowed to exclude 100 percent of their Social Security benefits. For taxpayers with provisional income between the first and second tier thresholds, the amount of benefits subject to federal tax equals the lesser of:

- 50 percent of provisional income over the first tier threshold; or

- 50 percent of Social Security benefits.

For taxpayers with provisional income above the second tier threshold, the amount of benefits subject to federal tax equals the lesser of:

- 85 percent of provisional income over the second tier threshold, plus 50 percent of the difference between the second and first tier thresholds; or

- 85 percent of benefits.

Provisional Income

Provisional income is a federal definition of income equal to FAGI, excluding taxable Social Security benefits, plus certain “above-the-line” deductions, plus nontaxable interest, plus 50 percent of Social Security benefits. The deductions that are added back in calculating provisional income are: adoption expenses, student loan interest, tuition expenses, certain foreign income, and income from Puerto Rico and certain other U.S. territories. The formula for provisional income is as follows:

Provisional Income

= FAGI-Taxable Social Security Benefits + 50% of Social Security Benefits + Nontaxable Interest + Certain "Above the Line" Deductions

History of Federal Treatment

Social Security benefits were exempt from federal income taxes prior to 1983, when Congress subjected a portion of benefits to federal tax. The Social Security Amendments of 1983 subjected up to 50 percent of a taxpayer’s Social Security benefits to federal taxes, beginning in 1984. The amendments subject only Title II Social Security benefits and Tier 1 Railroad Retirement benefits to this treatment. Title II benefits are Old-age, Survivor’s and Disability benefits—they do not include Supplemental Security Income (SSI). The Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993 added the second tier to the federal calculation, which subjected up to 85 percent of taxpayer’s Social Security benefits to federal tax.

Taxpayer Example Lookup

The following tool estimates state income tax liability for a taxpayer with social security income.

Tax Treatment of Social Security in Other States

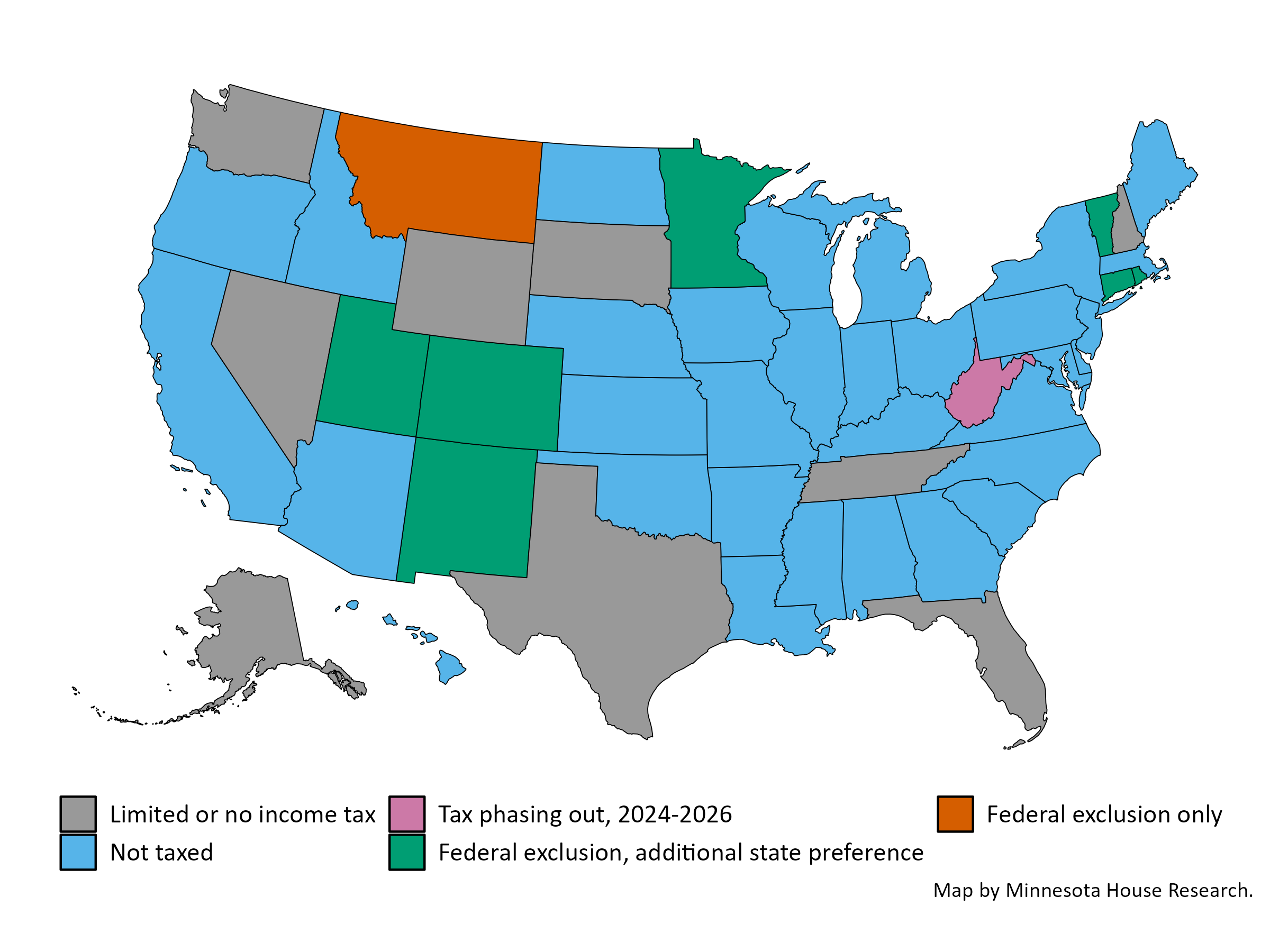

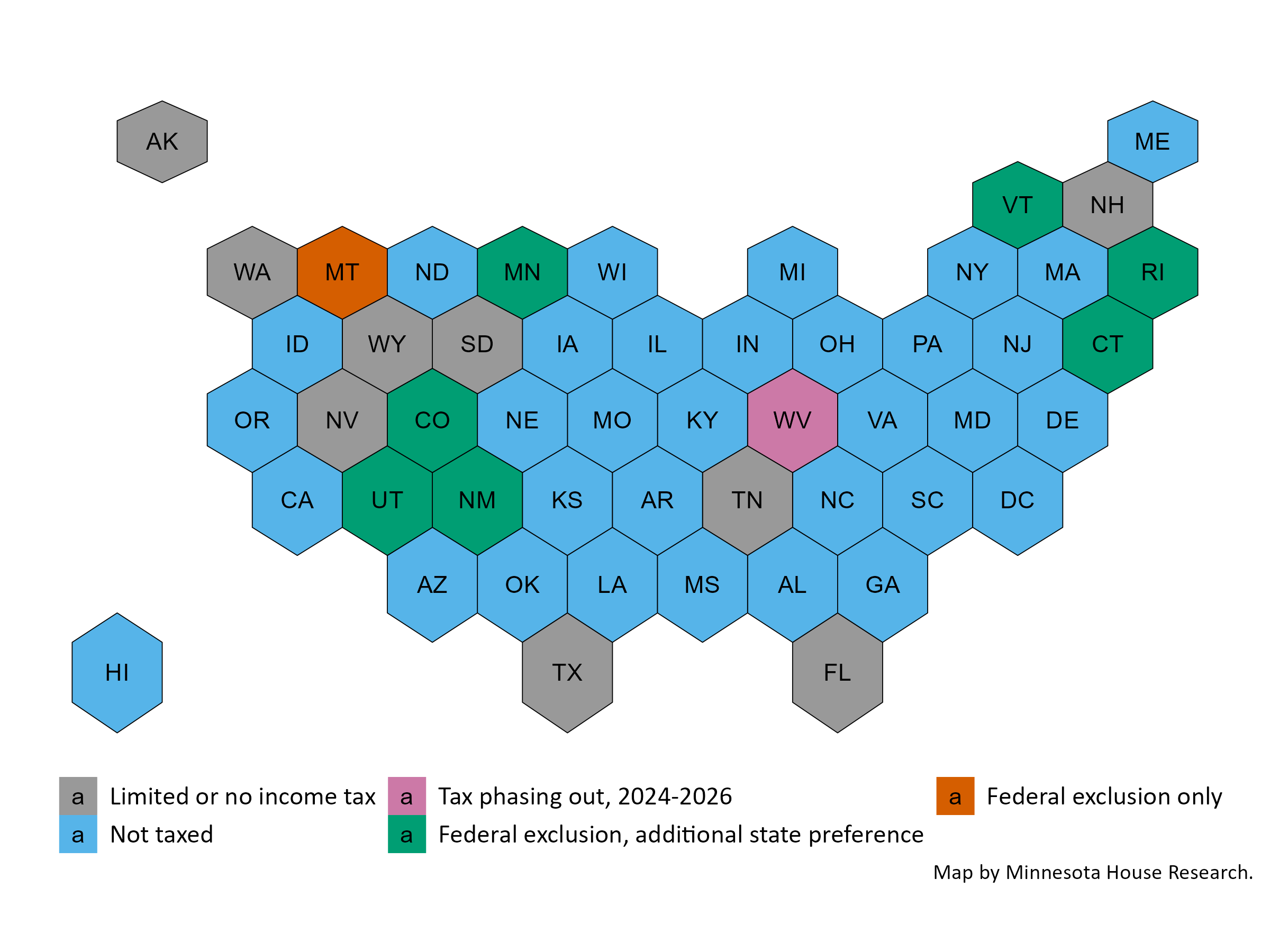

Figures 3 and 4 below show the different tax treatments for Social Security benefits in the various states.

Nine states do not have an income tax or have a tax limited to specific kinds of unearned income.

The states are Alaska, Florida, Nevada, New Hampshire, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming.

Thirty-two states with an income tax, plus the District of Columbia, fully exempt Social Security benefits from the individual income tax.

The states are Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Delaware, District of Columbia, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky,

Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma,

Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Virginia, and Wisconsin.

As of 2024, nine states subject at least a portion of Social Security to state taxes, one of which is scheduled to allow a full exemption in 2026. With the

exception of Montana, most states in this group (Colorado, Connecticut, Minnesota, New Mexico, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Vermont, and West Virginia) allow the federal exclusion,

but offer additional deductions, credits, or exemptions for Social Security income, and for taxpayers of certain ages or below certain income levels.

Table 5 describes these preferences in detail.

Table 5: State tax preferences for Social Security or retirees

| State |

Type of Benefit |

Description |

| Colorado |

Retirement income preference |

Taxpayers ages 65 and older may subtract up to $24,000 of taxable pension and annuity income (including Social Security).

Taxpayers ages 55 to 65 may subtract up to $20,000 of the taxable pension and annuity income.11 |

| Connecticut |

Income-tested exemption |

Exempt for married taxpayers with less than $100,000 of AGI and singles with $75,000 of AGI. Subtraction is phased out above those thresholds.12 |

| Minnesota |

Income-tested exemption |

Social Security benefits are 100% exempt from state income taxes for taxpayers under certain income thresholds. For tax year 2025, married

joint filers do not pay tax on their benefits if their adjusted gross income is $105,380 or less; for single and head of household taxpayers, the threshold is $82,190.13 |

| Montana |

Federal exemption only |

Allows the federal exemption and does not have a state-specific exclusion. Montana provides a state tax subtraction (used to determine state taxable income)

of $5,660 for taxpayers 65 years old and older in tax year 2024.14 |

| New Mexico |

Exemption for senior taxpayers |

Federally taxable benefits are 100% exempt for married joint taxpayers with $150,000 or less of adjusted gross income and other taxpayers with $100,000 or less of adjusted gross income.15

New Mexico also allows an exemption amount of up to $8,000 for low-income senior taxpayers (adjusted gross incomes below $30,000 for married joint filers and $18,00 for single filers). |

| Rhode Island |

Income-tested exemption |

Exempt for married taxpayers 65 or older with $130,250 of AGI and single/head of household taxpayers with $104,200 of AGI. (Tax year 2024; thresholds are adjusted for inflation.)16 |

| Utah |

Social Security credit |

Taxes the same amount of benefits as are taxable federally, but allows taxpayers to claim a “Social Security Credit” equal to 4.55% (the state income tax rate)

of federally taxable Social Security benefits. The credit is phased out at $75,000 for married joint filers and surviving spouses, and $37,500 for all other filers.17 |

| Vermont |

Income-tested exemption |

Exempt for married joint taxpayers with less than $75,000 of AGI and singles with $65,000 of AGI. Exemption is phased out above those thresholds.18 |

| West Virginia |

Income-tested exemption, with scheduled phase-in of full exemption |

For tax year 2024, taxpayers with $100,000 of adjusted gross income (married joint) or $50,000 of adjusted gross income (other filers) receive a deduction for 100% of

federally taxable benefits. Taxpayers above those income amounts receive an exemption for 35% of federally taxable benefits.19 Under current West Virginia law, the exemption

for those above the income limit will increase to 65% in tax year 2025, and will reach 100% in tax year 2026 (making all Social Security income nontaxable).20 |

Figure 3: State Tax Treatment of Social Security Income (Traditional Map)

Figure 4: State Tax Treatment of Social Security Income (Hexagonal Map)

Legislative History of the Minnesota Subtraction

2017 Legislature: Subtraction Established

The legislature established the Minnesota Social Security Subtraction in the 2017 omnibus tax bill.21 The original subtraction was for up to $4,500 in federally taxable benefits for married couples filing joint returns and $3,500 for single taxpayers and heads of household. The maximum subtraction was phased out beginning at $77,000 for married couples filing joint returns and $60,200 for single taxpayers and heads of household. The legislature indexed both the maximum subtraction and phaseout thresholds for inflation.

2019 Legislature: Expansion of Maximums

The 2019 omnibus tax bill increased the maximum subtraction amounts, while slightly reducing the phaseout thresholds.22 The Department of Revenue estimated that the increase in the subtraction resulted in a revenue reduction of about $4.4 million in tax year 2019, and would grow to $5.3 million in FY 2023.

The bill increased the maximum subtraction by $450 for married taxpayers filing joint returns and $360 for single taxpayers and heads of household. The legislature additionally reduced the phaseout thresholds by $2,250 for married couples filing joint returns and $1,800 for single taxpayers and heads of households. The reduction in the phaseout thresholds did not reduce any taxpayer’s subtraction—it denied the benefit of the increase in the maximum subtraction to taxpayers above the phaseout thresholds

2023 Legislature: Significant restructuring of Social Security subtraction

The 2023 omnibus tax bill significantly expanded the subtraction and established a new “simplified” method for calculating the subtraction.

This put in place the current structure, where taxpayers with incomes below a particular threshold receive a 100 percent Social Security subtraction,

which is phased down in increments of 10 percent of benefits. At the time the law was enacted, the phaseout began at $100,000 for married joint filers

and $78,000 for single and head of household filers. The law also included a hold harmless provision, called the “alternative subtraction” that allowed

taxpayers to continue to calculate their subtraction under the old law formula.

The Department of Revenue estimated at the time of enactment that the new subtraction reduced revenue by $235.8 million in tax year 2023 and $260.4 million

in tax year 2024, and that about 321,950 returns would receive an average tax reduction of $732.

History of Social Security Taxation in Minnesota

Minnesota historically conformed to the federal tax treatment of Social Security income. For tax years 1983 and prior, Social Security benefits were exempt from tax at the federal and state level. Beginning in tax year 1984, Congress subjected Social Security benefits to federal tax. Minnesota initially did not conform to the federal treatment, and for tax year 1984, the state allowed a subtraction for Social Security benefits that were taxable federally. In 1985, the state repealed the subtraction, and followed the federal treatment until tax year 2017. The 2017 legislature established a state subtraction for a portion of taxable benefits, effective in tax year 2017.

Table 6: Historical Tax Treatment of Social Security Benefits

| Tax Year |

Federal Tax Treatment |

Minnesota Tax Treatment |

| 1983 and prior |

Fully exempt |

Fully exempt |

| 1984 |

Up to 50% of benefits taxed |

Fully exempt |

| 1985-1993 |

Up to 50% of benefits taxed |

Up to 50% of benefits taxed |

| 1994-2016 |

Up to 85% of benefits taxed |

Up to 85% of benefits taxed |

| 2017 and later |

Up to 85% of benefits taxed |

Up to 85% of benefits taxed, less state subtraction for amounts taxable federally |

Footnotes

1 House Research modeling for tax year 2025 using the House Income Tax Simulation (HITS) model, version 7.5 and November forecast assumptions.

3 The Social Security Administration reported that 1,123,666 beneficiaries received OASDI Social Security benefits in Minnesota as of December 2023. Because many of those individuals filed joint income tax returns, the estimate of 863,100 returns is plausible. Social Security Administration, Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin, 2024, December 2024, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2024/supplement24.pdf.

4 Return data estimated using the House Income Tax Simulation model (HITS), version 7.5.

5 Based on House Research estimates of the number of beneficiaries.

6 House Research modeling for tax year 2022 estimated that about $17.535 billion in total Social Security income was reported on resident returns, while the Social Security actuary estimated that $21.555 billion in benefits was paid to Minnesota residents that year. Social Security Administration, Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin, 2023, November 2023, Table 5.J1, https://www.ssa.gov/policy/docs/statcomps/supplement/2023/supplement23.pdf.

7 The 2024 Social Security Statistical Supplement reported $24.342 billion in benefits paid to Minnesota residents in 2023, and 1,123,666 Minnesota beneficiaries as of December 2023. This implies an average benefit of $21,663, which was rounded to $21,700. For a married couple filing a joint return, the graph assumes twice the average benefit amount, or $43,400, of Social Security benefits.

9 Paul Davies, Congressional Research Service, "Social Security: Taxation of Benefits," November 1, 2019.

11 Colorado Department of Revenue, Taxation Division, “Income Tax Topics: Social Security, Pensions, and Annuities," February 2024.

14 Montana Department of Revenue, Form 2 and Form 2 Instructions.

16 Rhode Island Division of Taxation, 2024 Modification Worksheet: Taxable Social Security Income Worksheet.

17 Utah Code section 59-10-1042.

January 2025